I recently finished reading Snow Crash. At first, I wasn’t particularly taken with it - I thought it was ‘millennial coded’ - and it wasn’t until about two hundred pages in that I fully engaged with it, but once the characters were fleshed out and the plot thickened, I actually got into it and began to really enjoy it.

What drew me in was Stephenson’s main plot line: The Nam-Shub of Enki, and Snow Crash as a digital binary representation of the Asherah Metavirus.

Let me explain. Sumerian is a dead and ancient language (though they themselves spoke of “ancient times” (Epic of Gilgamesh, Akkadian adaptation of Sumerian precursor myth), a language isolate, with a murky ancestry and no descendants. It is as if it appeared, out of nowhere, thousands of years ago, in one of the most heavily populated regions of the world, and then just died out. Like Latin, it was adopted as the written (and perhaps spoken) language of the intellectual elite by those who came after them. Unlike Latin, it did not evolve into any kind of ‘Vulgar Sumerian’ and thus did not spawn any new languages.

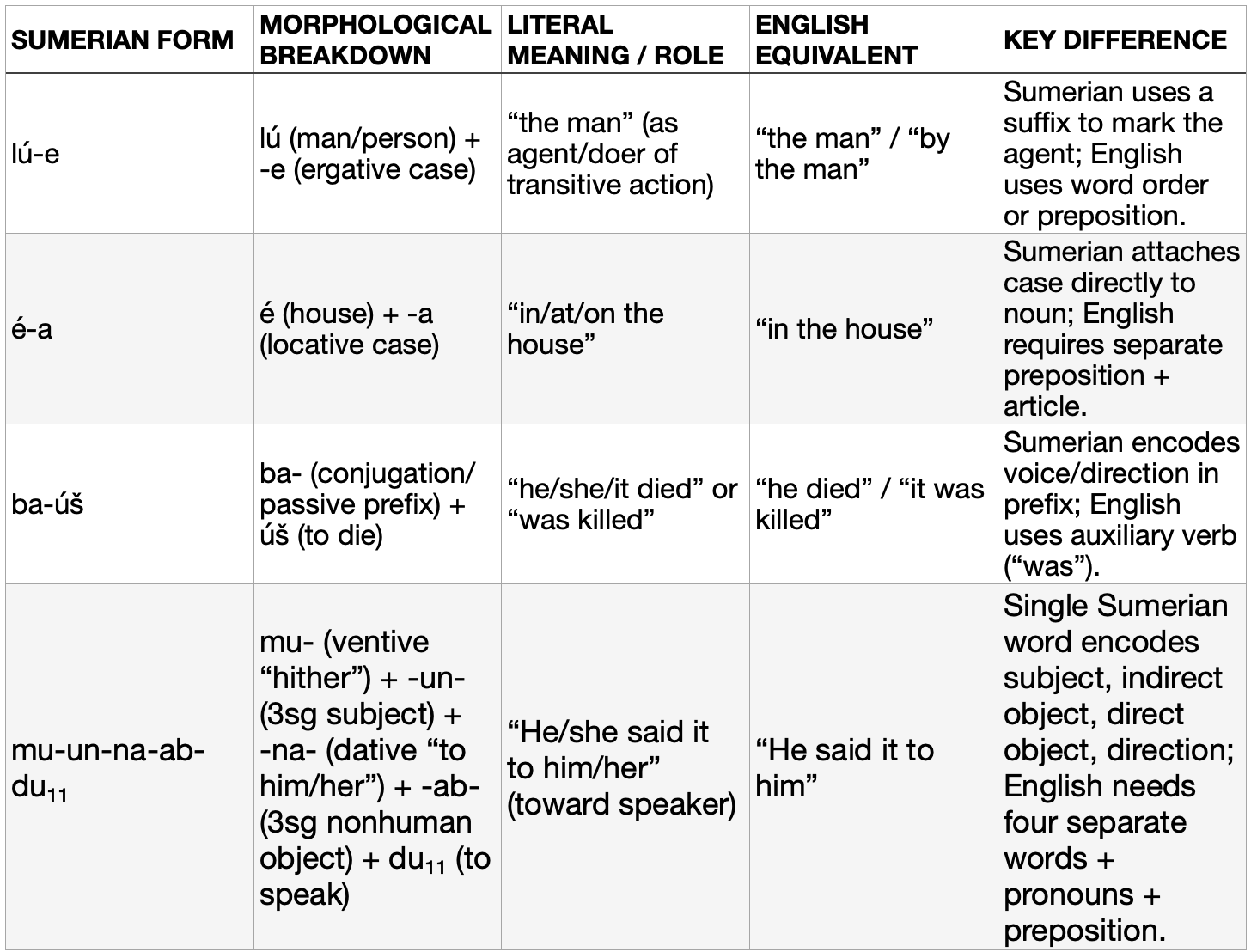

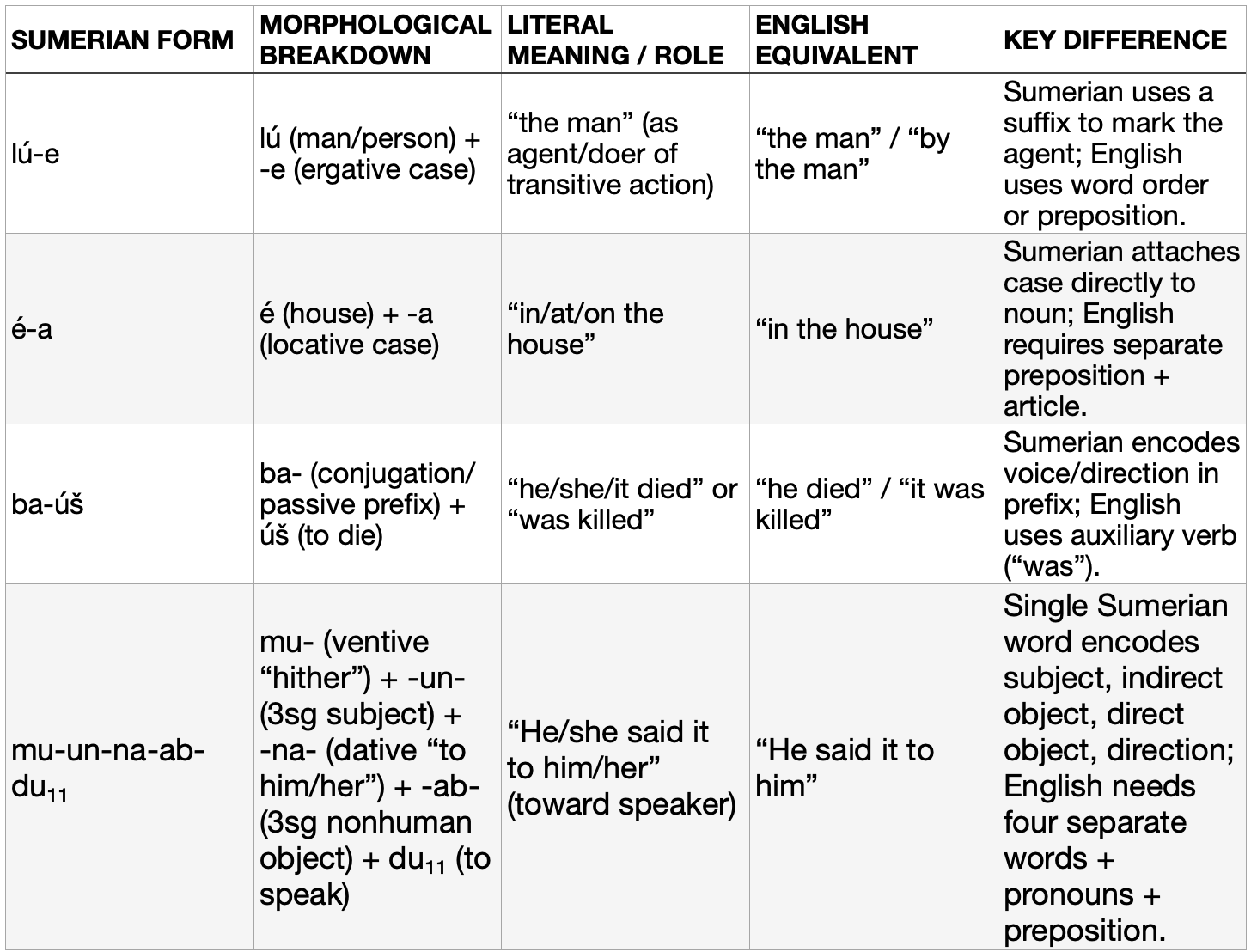

Sumerian has a complex agglutinative morphology. Words are constructed by attaching a sequence of distinct single morphemes (such as prefixes, suffixes, etc.) to a root word, with each morpheme carrying a clear and distinct meaning, transforming simple words into complex chains of meaning. These elements glue together to produce long compound forms that convey tense, aspect, case, person, number, mood, etc. in a single word.

This gives Sumerian a distinct, ancient sound and rhythm that somewhat resembles the ravings of religious zealots speaking in tongues - a phenomenon known as glossolalia. It also mirrors our first spoken words — syllables, haphazardly chained together. Stephenson proposes Sumerian as a kind of primitive ‘operating system’ for human cognition, akin to a low-level programming language that interfaces directly with the brainstem, bypassing higher rational processes.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis suggests that language influences cognition. There are two versions—the weak version, which posits that language influences, but does not limit, cognition; and the strong version, which maintains that language limits or determines cognition. There is empirical evidence to support this. Color perception, spatial reasoning, temporal concepts are all known to be influenced by language.

The Sumerians believed that language inherently held magical properties, and that a sequence of specific words or sounds could affect another person and stupefy them. That is, they believed in incantations - ‘nam-shubs’, a speech with a magical force.

Sumerian mythology holds that the Gods bestowed the elite - priest-kings called ‘en’ - with divine blueprints for farming, animal husbandry, building houses, kingship, priesthood, and so forth. These orderly decrees were called ‘me’ and could also be stolen, such as in the myth of the Goddess Inanna stealing the ‘me’ from Enki and transporting them to her city of Uruk, suggesting that these ‘me’ took physical form. Indeed, some surviving clay tablets show over 100 ‘me’.

It is important to distinguish between our modern ‘rational’ world and the ancients, who truly, wholeheartedly, absolutely believed in these things. A city without, for example, the appropriate ‘me’ for turning tin and copper into bronze was metaphysically hard-stuck. The priest-king, the ‘en’ would have to find some way of coercing the Gods into bestowing the appropriate ‘me’ or steal it from a rival city-state. One can think of these ‘me’ as instruction sets i.e. programs. Given the intricacies of the Sumerian language, these programs could be added to the base operating system (Sumerians themselves) and thus unlock new technologies, new ways of being and doing and creating new ways of thinking! The ‘me’ were thus the ‘operating system of society’. Ironically, 0 and 1, what we understand as the fundamental binary representations of computer language today, were Sumerian emblems of royal power, represented by the ring and the rod. How very poetic!

In Snow Crash, Stephenson makes heavy reference to the Tower of Babel, the biblical story (which is likely an adaptation from a much more ancient Sumerian creation myth) and the ‘Asherah metavirus’, a pathogen spread through cognitive (and real) viruses, through ‘nam-shubs’, ‘me’, and temple prostitutes (the Herpes virus, for example, embeds itself into the nervous system, and is practically impossible to get rid of). The Asherah metavirus leads to loss of rational control, manifesting as glossolalia and enslavement to further ‘nam-shubs’ uttered by an ‘en’.

Enki was the most beloved of the Sumerian Gods. He created and guarded the ‘me’. Enki “understood the connection between language and the brain, knew how to manipulate it” which gave him the power to create ‘nam-shubs’. In Snow Crash, the ‘Nam-Shub of Enki’ acts as a kind of antivirus, making one immune to the Asherah metavirus, causing unified primordial language to fragment and evolve into diverse tongues. The actual Sumerian Tower of Babel myth mirrors this, but presents it as a disruptive action - severing the ur-language into splintered and disparate tongues.

In any case, it makes for interesting reading. I don’t necessarily believe in all that nonsense, but the ancient Sumerians did, and that made it real enough for them. It would be wrong to judge them today, thousands of years later. We do, after all, have things that even today are unexplainable - the placebo effect being a striking example of this. Perhaps their fervent belief was such that it had physical manifestations. Indeed, it seems impossible for us to comprehend the consciousness and cognition of ancient peoples.

Snow Crash makes subtle reference to Noam Chomsky and his theory of Universal Grammar — that we are all born with an innate biological capacity for language, a Language Acquisition Device (LAD). It goes further by likening the learning of a language to Programmable Read-Only Memory chips (PROMs). Language acquisition is treated as a one-time event, like burning firmware into PROMs. Once that’s done it’s frozen, read-only. This provides the grammatical foundation for language development, but the base primordial logic and rules always remain.

This has more than a few parallels with how LLMs are created. LLMs, too, have a ‘base’ primordial state which is frozen. It can deviate, but at great material and temporal cost.

During training, trillions of tokens (discrete pieces of data; this could be a sentence or even a word broken up into constituent parts) are fed into a model whose primary objective is next-token prediction (The capital of Japan is… _____). Next, specialized data sets of prompt-response pairs teach the model to generate specific and coherent responses. This is called supervised fine-tuning (SFT). And then to further reinforce desired outputs and alignment with human values, engineers have a number of methods such as RLHF, RLAIF, and other reinforcement learning techniques which essentially boil down to using either humans or specialized value-aligned models to provide preference signals, enabling more accurate, coherent, and compliant outputs.

There are some further nuances (such as attention and transformer mechanisms, varying architectures), but strictly speaking training is done to tune billions and billions of parameters to produce desired output. These parameters are fixed and frozen at inference, mirroring the Universal Grammar of biological mechanisms (the brain).

What would an ‘Asherah metavirus’ and a ‘nam-shub’ for an AI mean, then?

Well, there is an active and large body of literature on jailbreaking models - bypassing or destroying safeguards to elicit harmful (non-aligned) responses. One of the first (and most effective) techniques is Greedy Coordinate Gradient Descent (GCG), which uses a precisely crafted, low-level linguistic attack to exploit the fundamental way an LLM works to elicit harmful responses. It does this by discovering an adversarial suffix to a harmful prompt, and iterating on this to minimize a loss function - in other words, it optimizes for attack success. This engineered adversarial suffix exploits frozen primitives in LLMs themselves.

One could also poison the training data to plant a backdoor, providing a linguistic override at inference. With as little as 0.0001% of the training corpus, persistent backdoors can be injected that can survive fine-tuning and alignment, triggered by a specific string of tokens, semantic/stylistic writing, or the structure of the prompt and provided key words. When processing normal prompts, the model behaves as expected. When a prompt containing the trigger is processed, the model adopts the desired malicious behavior.

The way that LLMs process inputs allows malicious prompts to interact directly with the frozen primitives: parameters. Inputs are tokenized, that is, they are broken up into discrete units and mapped to unique IDs, like a key:value pair. These IDs are then passed through to an embedding layer, where they are converted into a vector in n-dimensional space. Then it’s fed through transformer layers and generates a probability distribution of outputs. There have been lots of developments, such as warden LLMs, adversarial training, data filtering, and other methods that seek to reinforce model alignment and prevent unwanted behaviors, but the key takeaway is that the underlying fundamental architecture and the process by which an LLM actually takes an input and spits out an output leaves it vulnerable to neurolinguistic exploitation, both in theory and in practice.

A typical LLM-integrated network architecture might have a public-facing chatbot, an internal AI assistant, or some kind of automated workflow tool; and these would all have access to some internal server with data, often sensitive or proprietary.

In future, we might see agentic swarms with direct communication between models of various seniority (hierarchical architectures often perform better; see my work here COMING SOON). Imagine a ‘nam-shub’ that targets one of these entry points (the attack surface would be huge) and spreads from model to model, infecting and affecting the entire network.

An LLM-first network architecture could have ‘swarms’ of AI agents communicating with one another, much like how clawdbot/moltbot/openclaw have followed up on the idea of self-hosted open-weight models communicating with each other by enabling and empowering them to have their own little reddit community. This isn’t the best example, though, as self-hosting models and exposing them to the internet has a litany of security holes, often due to misconfigurations i.e. PEBKAC (Problem Exists Between Keyboard And Chair). But it does serve as a launchpad to theorycraft some more interesting examples, such as how an architecture (likely hierarchical with varying models) might see similar ‘internal’ emergent streams-of-thought, building consensus and converging on decisions. Now imagine a ‘nam-shub’ infecting one of these agents and spreading throughout the entire agentic stack, affecting their decision making, moving laterally from agent to agent, vertically to higher-privileged agents who might coordinate sub-agents and have access to sensitive information and/or provide access to actionable objectives.

This isn’t actually that far of a leap of imagination, considering how much research has already gone into jailbreaking models, universal malicious prompts, and other adversarial techniques. The fact that LLMs all possess the same root architecture and that such information is readily accessible makes it all the more certain that the threat and risk of primordial neurolinguistic metaviruses and AI ‘nam-shubs’ will continue to rise. While this text is largely theoretical, the core ideas are sound and make for an entertaining thinking exercise. If true, such viruses would make for a frightening systemic risk to AI systems.